Sinologist Martin Kern (right) and Jiang Lujing, research librarian from the Jingzhou Museum in Hubei province, examine Warring States Period (475-221 BC) bamboo manuscripts of the Shi Jing at the museum in January. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Scholars explore evolution of textual culture, and its transition from memorization to individual contemplation, Fang Aiqing reports in Suzhou, Jiangsu.

It is so natural these days to read a book that people take doing so for granted, barely thinking about how and when the earliest books came into being. While the elements of reading — content and connotation, knowledge and spiritual inspiration — have been closely examined for centuries around the world, in recent decades, scholars have turned their attention to the origins and evolution of books, as well as to the act of reading itself.

In the case of ancient China, although the oracle bone scripts — the earliest writing system known in the country — can be traced back around 3,300 years, and a textual culture formed thereafter, it took many more centuries before the earliest examples of what could be called "books" appeared.

Some of China's greatest thinkers — for example, Confucius and Lao Tzu — emerged during the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) and the Warring States Period (475-221 BC).

Sinologist Martin Kern, professor at Princeton University and codirector of the International Center for the Study of Ancient Text Cultures of Renmin University of China, argues that it is arbitrary for modern people to unequivocally attribute The Analects of Confucius to Confucius and his disciples, or similarly, to attribute the philosophical text Tao Te Ching to Lao Tzu.

He stresses the need to separate the thoughts of the great thinkers from the writing of the earliest books in which those thoughts appear.

In a speech at an academic forum themed "From Practices to Things: First Books in the Ancient World" at the RUC's Suzhou Campus in Jiangsu province in late August, Kern talked about what may be the creation of books in ancient China, by using the example of Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) official Liu Xiang (77-6 BC), who compiled a number of books with a team of scholars under the command of the emperor starting in 26 BC.

Kern defined the concept of an early book as a larger textual unit constituted of smaller textual units that people now call "chapters".

Each of the textual units Liu and colleagues collated were distilled from multiple editions, which they compared, excising anything that they thought was duplicated or contradictory, before they finished the collation. Then they arranged these units in order, gave each one a title, and combined them in the form of an anthology that they also named.

"The texts came from the Warring States Period, or even earlier, but were reconstituted in a form in which they had never used before," Kern says.

He then calls for attention to the challenge Liu encountered when trying to put the texts in order. Before book culture flourished, it was common for many philosophical texts to be fragmented, or to appear in different versions whose contents varied greatly.

Kern interprets bamboo manuscripts dating back to the Warring States Period during a forum on ancient textual culture in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, on Aug 28. [PHOTO BY FANG AIQING/CHINA DAILY]

While they are similar in terms of words and sentences, they differ in the sequence of paragraphs and chapters. Yet, ancient bamboo manuscripts reveal that people at the time already possessed a sense of textual integrity, and would therefore have undertaken additional proofreading and other precautionary measures to ensure the texts did not become disordered.

Kern points out that there's no real reason to privilege any of the versions, including the received one, over the others. None of the written versions was more authoritative, and none can be considered earlier, or better.

Xu Jianwei, a professor at the Renmin University of China's School of Liberal Arts, speaks at a workshop on the same topic on Aug 25. [Photo provided to China Daily]

A similar situation applies to the Shi Jing, which is said to be a compilation of ancient poetry by Confucius. Also known as The Book of Songs or the Classic of Poetry, the early version of the book was comprised of 311 pieces of music dating from the 11th to the 6th century BC — six of which were purely instrumental. These were mainly folk ballads and ritual hymns with grand narratives that were designed to be sung and danced to during sacrificial ceremonies.

It's widely believed that Confucius chose from among the popular songs of the time and introduced them into his collection of poetry, endowing them with a new textual structure and political, moral or ethical significance. The Shi Jing is one of China's earliest books.

Since the 2nd century BC, its textual tradition began to dominate, and the musical component was gradually lost. Oral transmission remained crucial to the book's spread until the 7th century, according to Xu Jianwei, professor at the School of Liberal Arts at the RUC.

Kern says that oral form of the Shi Jing did not vary greatly, but its written form did. Chinese contains a large number of homophones — different characters with the same sound — and so transcription depended on what the scribes thought they had heard when the text was recited, and they transcribed it according to this understanding. Therefore, interpretation was highly localized and often idiosyncratic.

"There was great tolerance for the fact that people could encounter the same story, the same problem, and the same philosophical argument in multiple contexts, and always in a different way," Kern says.

He adds that this indicates the absence of emphasis on authorship in early China. People seldom asked who had written a text, nor was the author's name included on bamboo or silk manuscripts, which is very different from the ancient Greek and Arabic traditions.

"The authority of early Chinese texts derived not from their authors, but from the tradition inspired by the thoughts of the great philosophers," Kern says.

For his part, Xu expounded on how the Shi Jing evolved into the book people read today.

Four mainstream textual versions were developed around the 2nd century BC.Among them was one that scholars Mao Heng and his nephew Mao Chang annotated at the beginning of the Western Han Dynasty. Centuries later, Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) Confucian scholar Zheng Xuan (127-200) completed his own annotation of the Shi Jing based on this earlier work. Known as the Mao Shi Zhuan Jian, Zheng's version gradually became the standard rendition that is read until today.

For each sentence in Mao Shi Zhuan Jian, Zheng paralleled the original text of the Shi Jing, the Mao annotation, as well as adding his own annotations. He also added an annotation to repeated words and sentences each time they appear, so that readers don't have to look them up again, and can start reading wherever they want. He also ensured that the annotations constituted a coherent meaning system free of contradictions.

Xu says that Zheng's version was intended for independent reading, a major transformation in the transmission of knowledge in ancient China.

Before that, memorization and oral transmission were central. When Western Han Dynasty scholar-official Dongfang Shuo (154-93 BC) offered his services to the emperor, he claimed that, at the age of 19, he could recite 440,000 characters of the classics, including the arts of war.

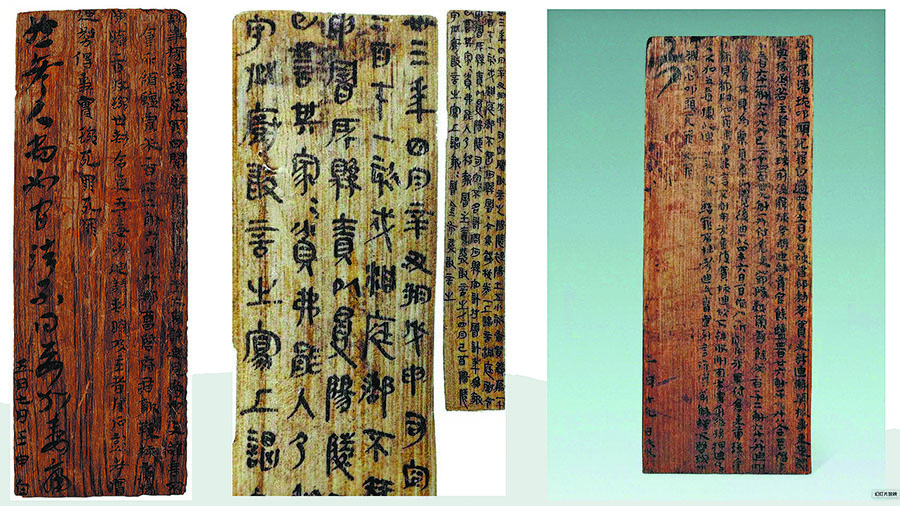

Wooden tablets dating back to the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) unearthed in the ancient town of Liye in Hunan province. Some 20 centimeters long, they were portable and easy to read. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Scholars speculate that these strips were used in an educational environment. Teachers would place them on the ground or hang them on a wall, so that all of the students could see them in class.

Xu explains that the use of paper gradually replaced bamboo strips and wooden tablets, lowering the cost of reading, adding that the spread of reading may have resulted not only from increasing literacy, but also from the increased demand for standardized texts due to stricter selection procedures being implemented in the entrance exams for officials.

"The whole way of learning and reading changed, and ever since, books have been made for reading, rather than for being displayed or recited," Xu says.

He says that over the past 30 years, the global academic circle of humanities has placed increasing emphasis on the importance of the carriers of reading and writing — the ways ancient people read and wrote; how knowledge was transcribed, copied and circulated; and how reading and writing became a social practice that accelerated the development of civilizations — rather than learning about the past simply by reading ancient documents.

The development of archaeology and the numerous subsequent discoveries have played an important role in this process.

"Archaeology is the foundation of a lot of our work today, so that we not only study new things, but also rethink traditional things that we thought we knew," Kern says.

"We have to take the materials we find seriously in their own right, and for what they are, not for what we want them to be. We should let them speak, and help us ask new questions about tradition, instead of going with our traditional presumptions into the texts. The nature of scholarship is to doubt things, to ask questions, not to prove things."